Heap

We have implemented a major change to the way Firefox manages JavaScript objects. JavaScript objects include script-instantiated objects such as Arrays or Date objects, but also include JavaScript representations of Document Object Model (DOM) elements, such as input fields or DIV elements. In the past, Firefox held all JavaScript objects in a single JavaScript heap. This heap is occasionally garbage collected, which means the browser walks the entire object graph in the heap and determines which objects are still reachable and which are not. Unreachable objects are de-allocated and space is reclaimed.

Having all JavaScript objects in the browser congregate in a single heap is suboptimal for a number of reasons. If a user has multiple windows (or tabs) open, and one of these windows (or tabs) created a lot of objects, it is likely that many of these objects are no longer reachable (garbage). When the browser detects such a state, it will initiate a garbage collection. Unfortunately though, since objects from different windows (or tabs) are intermixed in the heap, the browser has to walk the entire heap. If a number of idle windows are open, this can be quite wasteful, since those windows haven’t really created any garbage, so whenever a window with heavy activity triggers a garbage collection, much of the garbage collection time is spent walking unrelated parts of the global object graph.

In Firefox this problem is even more pronounced than in other browsers, because our UI code (also called chrome code, not to be confused with Google Chrome) is implemented in JavaScript, and there are a lot of chrome (UI) objects alive at any given moment. These UI objects tend to stick around and every time a web content window causes a garbage collection, Firefox spends a lot of time figuring out whether chrome objects are still alive instead of being able to focus on the active web content window.

Compartments

For Firefox 4 we changed the way JavaScript objects are managed. Our JavaScript engine SpiderMonkey (sometimes also called TraceMonkey and JägerMonkey, which are SpiderMonkey’s trace-compilation and baseline Just-in-Time compilers) now supports multiple JavaScript heaps, which we also call compartments. All objects that belong to a certain origin (such as “http://mail.google.com/” or “http://www.bank.com/”) are placed into a separate compartment. This has a couple very important implications.

- All objects created by a website reside within the same compartment and hence are located in the same memory region. This improves cache utilization by reducing false sharing of cache lines. False sharing occurs when we are trying to operate on an object and we have to read an entire cache line of data into the CPU cache. In the old model JavaScript objects could be co-located with arbitrary other JavaScript objects from other origins. Such cross origin objects are used together very infrequently, which reduces the number of cache hits we get. In the new model most objects touched by a website are tightly packed next to each other in memory, with no cross origin objects in between.

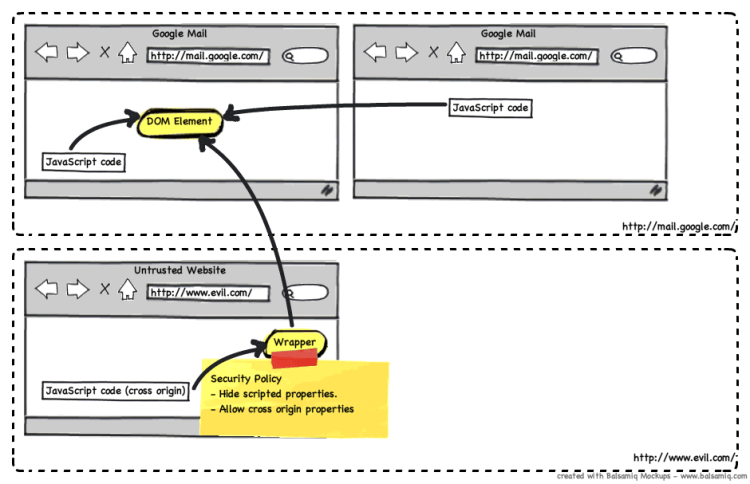

- JavaScript objects (including JavaScript functions, which are objects as well) are only allowed to touch objects in the same compartment. This invariant is very useful for security purposes. The JavaScript engine enforces this requirement at a very low level. It means that a “google.com” object can never accidentally leak into an untrusted website such as “evil.com”. Only a special object type can cross compartment boundaries. We call these objects cross compartment wrappers. We track the creation of these cross compartment wrappers, and thus the JavaScript engine knows at all times what objects from a compartment are kept alive by outside references (through cross compartment wrappers). This allows us to garbage collect individual compartments, in addition to a global collection. We simply assume all objects referenced from outside the compartment to be live, and then walk the object graph inside the compartment. Objects that are found to be disconnected from the graph are discarded. With this new per-compartment garbage collection we shortcut having to walk unrelated heap areas of a window (or tab) that triggered a garbage collection.

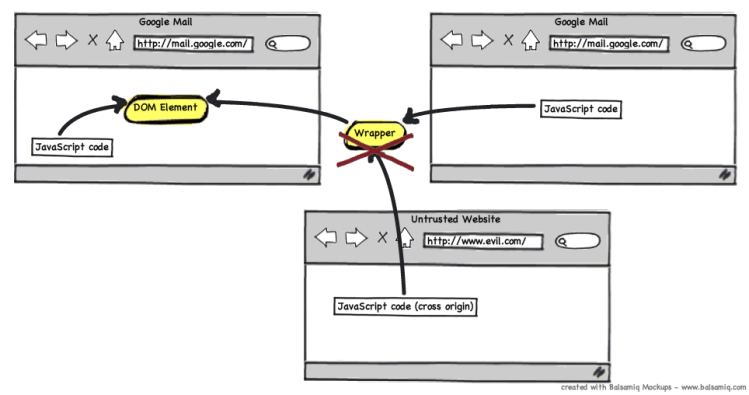

Wrappers

Wrappers are not a new concept in Firefox, or browsers in general. In the past we have already used them to regulate how windows (or tabs) pass objects to each other. In the past, when another window (or tab or iframe) tried to touch an object that belongs to a different window, we handed it a wrapper object instead. That wrapper object dynamically checks at access time whether the accessor window (also called the subject) is permitted to access the target object. If one Google Mail window is trying to access another Google Mail window, the access is permitted, because these two windows (or tabs or iframes) are same origin and hence its safe to permit this access. If an untrusted website obtains a reference to a Google Mail DOM element, we hand it the same wrapper, and if it ever tries to access the Google Mail DOM Element the wrapper will at access time deny the property access because the untrusted website “evil.com” is cross origin with “google.com”.

A disadvantage of the Firefox 3.6 wrapper approach (which is similar to the way other browsers utilize wrappers) was the fact that these wrappers had to be injected manually at the right places in the C++ browser implementation, and each wrapper had to do a dynamic security check at access time. With compartments we can do a lot better:

- Since all objects belonging to the same origin are within the same compartment, and no object from a different origin is in that compartment, we can let all objects within a compartment touch other objects in the same compartment without a wrapper in between. Keep in mind that this doesn’t just apply to windows but also to iframes. A single Google Mail session often uses dozens of iframes that all heavily exchange objects with each other. In the past we had to inject wrappers in between that kept performing dynamic security checks. This is no longer necessary, and there is an observable speedup when using iframe heavy web applications such as Google Mail.

- Since all cross origin objects are in a different compartment, any cross origin access that needs to perform a security check can only happen through a cross compartment wrapper. Such a cross compartment wrapper always lives in a source compartment, and accesses a single destination object. When we create a cross compartment wrapper, we consult with the wrapper factory to see what kind of security policy should be applied. When “evil.com” obtains a reference to a “google.com” object, for example, we have to create a wrapper to that object in the “evil.com” compartment. When that wrapper is created the wrapper factory will tell us to apply a stringent cross origin security policy, which makes it impossible for “evil.com” to glean information from the “google.com” window. In contrast to our old wrappers, this security policy is static. Since only “evil.com” objects ever see this wrapper, and it only points to one single DOM element in the destination compartment, the policy doesn’t have to be re-checked at access time. Instead, every time “evil.com” attempts to read information from the DOM element, the access is denied without even comparing the two origins.

Brain Transplants

A particularly interesting oddity of the JavaScript DOM representation is the existence of two objects for each DOM window (or tab or iframe), the inner window and the outer window. This split was implemented by web browsers a few years ago to securely deal with windows being navigated to a new URL. When such a navigation occurs, the inner window object inside the outer window is replaced with a new object, whereas the actual reference to window (which is the outer window) remains unchanged. If such a navigation takes the window to a new origin, we allocate the inner window in the appropriate new compartment. This of course creates now the problem that the outer window can possibly no longer directly point to the new inner window, because it is in a different compartment.

We solve this problem through brain transplants. Whenever an outer window navigates, we copy it into the new destination compartment. The object in the old compartment is transformed into a cross compartment wrapper that points to the newly created object in the destination compartment. So the term brain transplants is very appropriate here. We are essentially transplanting the guts of the outer window object into a new object hull in the same compartment we allocated the inner object in.

Processes

Some readers might wonder how compartments compare to per-tab processes as they are used by Google Chrome and Internet Explorer. Compartments are similar in many ways, but also very different. Both processes and compartments shield JavaScript objects against each other. The most important distinction is that processes offer a stronger separation enforced by the processor hardware, while compartments offer a pure software guarantee. However, on the upside compartments allow much more efficient cross compartment communication that processes code. With compartments cross origin websites can still communicate with each other with a small overhead (governed by certain cross origin access policy), while with processes cross-process JavaScript object access is either impossible or extremely expensive. In a modern browser you will likely see both forms of separation being applied. Two web sites that never have to talk to each other can live in separate processes, while cross origin websites that do want to communicate can use compartments to enhance security and performance.

Future

We have landed the main compartments patch and current nightly builds (and Beta 7) are running with per-origin compartment JavaScript heaps. Some of the functionality described above will not ship until Beta 8, most importantly per-compartment garbage collections. Those currently still happen for all compartments at once. The foundation we laid with the compartments work will also enable a number of future extensions. Since we now cleanly separate objects belonging to different tabs, future changes to our JavaScript engine will permit us to not only perform JavaScript garbage collection for individual compartments, but we will also be able to do so in the background on a different thread for tabs with inactive content (i.e. no event handler is firing at the moment).